Screenwriting ABCs Script Formatting

Inserts

Every once in a while a screenwriter will want the audience to read something a character is holding. Cases like this will call for a close-up of the letter, card, or note the character is looking at so that the audience can read it for themselves.

In this section we'll look at the right ways to show an Insert through the use of Subheadings, as well of some wrong ways that Inserts are often misused.

Inserting Something with Little Writing:

In general, no matter what you are inserting for the audience to read, you don't want it to have a ton of writing on it. There is nothing worse in film than to see a scene frozen for a good while in order to give the audience time to read a lengthy letter or article.

So when you DO use an Insert, make sure the item inserted can be read quickly, probably in 5 seconds or less (and that's pushing it).

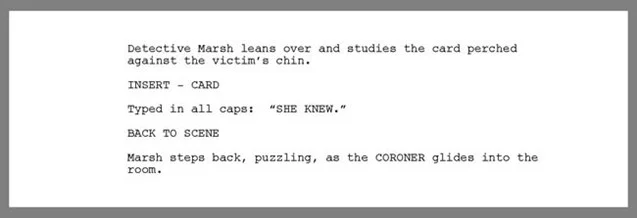

Here is a scene in which a serial killer has left a calling card for the detective to find:

That can easily be read by the audience in a glance lasting less than a second.

Notice the Subheading. I simple typed INSERT, then called out the subject of the Insert, which is CARD.

The phrase Typed in all caps: may not be necessary. After all, since I typed what is on the card in ALL CAPS and enclosed it in quotation marks, it should be shown on screen just as I've indicated. I wrote the phrase anyway to be sure. Had I not, I could have just said, It reads:.

After the insert, I then bring the reader BACK TO SCENE.

Longer Inserts:

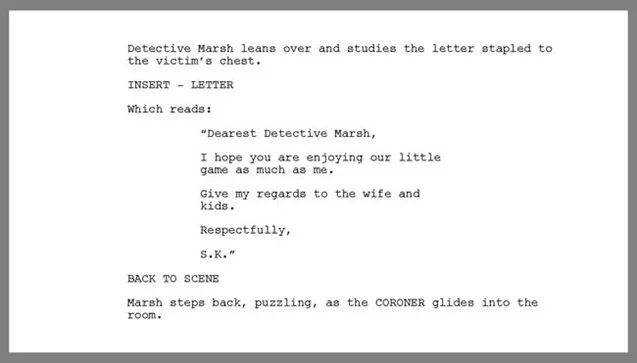

But let's say my serial killer and the detective are already somewhat acquainted, and he want to leave something a little longer and more intimate than a simple calling card.

In this case, a letter or note might be necessary, but remember to keep it short!

Here's how it might look on the page:

Although it is a letter, I've still kept it short and sweet. I think the audience will be able to read it quickly enough.

For the formatting of the content of the letter, it is indented as Dialogue, which isn't easy to do. I use Final Draft, and Final Draft doesn't let you write Dialogue without a Character Cue preceding it. So how did I do it?

First, I went ahead and wrote a Character Cue so that I could get to the Dialogue.

Then I wrote the letter as Dialogue, holding down Shift when I pressed Enter in order to create the double spaces within the Dialogue (so that it would look like a letter).

When I was finished writing the content of the letter, I highlighted the Character Cue and deleted it. The Dialogue segment remained.

There may be an different way to mess with the indentions, but this was a quick way to make it happen without having to delve into the inner workings of the Options or Preferences of Final Draft. After all, it's not like you'll use these Inserts many times in a screenplay.

Once the letter is complete, I again bring the reader BACK TO SCENE.

When the Letter Is Read Aloud:

Sometime, though, you'll want the audience to HEAR the letter being read, but not necessarily allow them to read it themselves. In cases such as this, the Insert isn't necessary, and may even be a little redundant.

Look at the same scene, re-written with a voice over.

Here I've dispensed with the Insert and create Dialogue in which the audience will hear the voice of the serial killer reading the letter as Detective Marsh reads it to himself. If Detective Marsh had read the letter on screen, we wouldn't have needed the (V.O.) cue.

However, had he read it to himself (we hear Marsh's thoughts as he reads the letter), then (V.O.) would have been needed.

Also, if we were seeing the letter as Marsh reads it aloud (again, a little redundant, but I digress) so that we hear his voice but don't see him speaking, we'd use the cue (O.S.) rather than (V.O.) to indicate his voice is coming from off screen.

At any rate, we DO NOT need to bring the audience BACK TO SCENE, since we never left the scene to begin with.

Common Ways to Misuse Inserts:

Often when I edit screenplays I'll run across Inserts where they shouldn't exist.

One of the most common misuses of the Insert is when the writer wishes to show the audience words written on a computer screen or text on a cell phone.

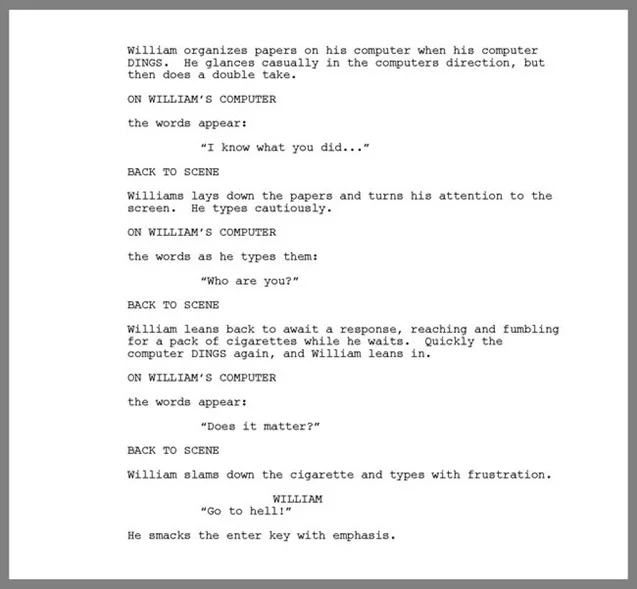

If you want to show a character having a computer chat conversation, here is the way the scene should be formatted:

Rather than using an Insert every time I want the camera focused on the computer, I use the Subheading ON WILLIAM'S COMPUTER.

The words on the computer are once again indented as Dialogue in the same manner as before. I could have also typed the words on the same line as the words appear: if I so chose to do so.

After each computer close-up, I bring the reader BACK TO SCENE.

The second time we see the computer screen, I indicated that the letters will appear as they are typed.

With William's last transmission, I decide to break the monotony of going to the screen again and indicate what William types by having him speak aloud what he is typing as he types it.

You'd format phone text messages in the same manner.

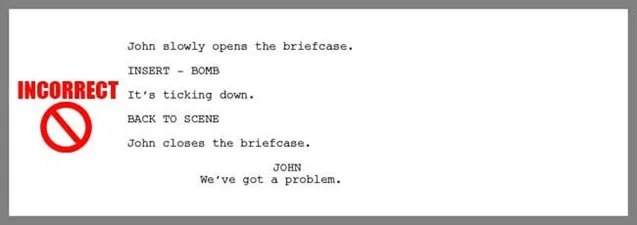

Another common way writers misuse Inserts is by inserting a random inanimate object that contains nothing to be read. It may be a shot glass, a gun, a knife, a pair of muddy shoes, etc. In situations such as this, the writer is using in Insert to indicate what is really just a close-up of a random item.

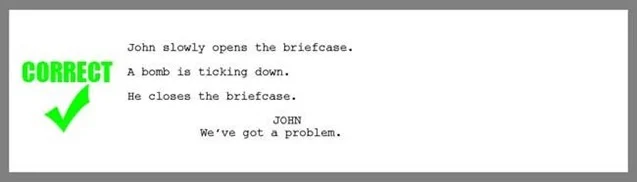

Here is a misused Insert:

Granted, a bomb isn't some random, everyday item (unless you live in the world of Airplane! in which bombs can be bought at the airport newsstand along with magazines and chewing gum). Even so, the circumstance doesn't call for an Insert.

Here is the same scene, simply written, so that the close-up of the bomb is implied:

Simple enough. The director has all the information he needs to know to briefly focus camera attention on the bomb.

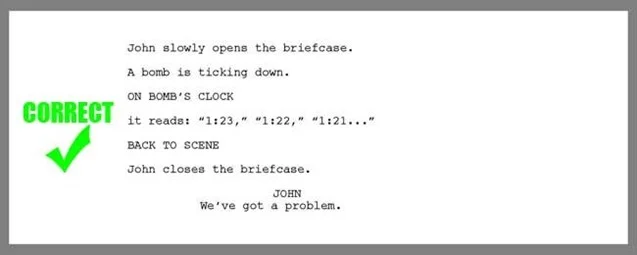

But what if there is a clock on the bomb that the audience needs to see so they know just how little time the character has to disable the bomb (or run like hell, given he's no MacGyver). Even then an Insert isn't necessary. You'd format the scene the same as you would a computer or text message.

Look at this example:

![]()

-------------------------------------

For more screenplay formatting rules and advice, check out the book, Your CUT TO: Is Showing! by T. J. Alex or visit www.scripttoolbox.com. From there, please like the page on Facebook, and share it with your friends.

If you have any formatting questions, please email T. J. at tj@tjalex.com.